Back in 1995, Nintendo almost cancelled Pokémon. The development had been rocky; beginning in 1989, the year the Game Boy was released, development had lasted right up to the end of the system's timespan (the Game Boy Pocket would be released the following year in 1996). It had missed the crucial 1995 Christmas season; Nintendo had gone full power into the then new Super Nintendo, and was rewarded with seven of ten of the year's bestsellers being SNES exclusives (such as Dragon Quest IV, Chrono Trigger). Only Virtua Fighter 2 and Tekken could edge into the top 10 from other systems, and they were both beaten in sales by Mortal Kombat 3, which was also a SNES game. The top selling Game Boy game in 1995 was Donkey Kong Land, whose reviews were okay, but nothing compared to its two parent games on the SNES; in the meanwhile, the Sega Nomad had made full 16-bit games portable, and the jokes about the low battery life disappeared into the ether of young gamers when they pulled NBA Jam or Streets of Rage out of their pocket. And Nintendo's Project Atlantis was well underway (though it, itself, would have its own rocky development process); to observers internal and external, the system was on its way out. And yet, a final release time was finally scheduled - to be buried in February of 1996.

To make the game more palatable to the 'tastes' of North American and European gamers, a rework was imagined. Cute, cuddly creatures would have been replaced with monsters inspired by Hollywood horror (faint elements of which are still visible in the inexplicable The Fly sequence the player must complete to advance the game); later, a complete regloss changing the game to electronic viruses from the internet was contemplated. But the president of Nintendo, Hiroshi Yamauchi, did not want to take this step. For one, it would have meant further delays. But for another, he was not a video game player; the only games he played were go and hanafuda. But he was an obsessive reader. To sell Pokémon, Mr. Yamauchi reasoned, they didn't need to chase a fad; they needed to sell the feeling of being young and hopeful, of seeing the world as an adventure. If they could sell the story, they could sell the game.

As word of mouth spread among completionists, RPG players, and the class of gamer that would be called "achivement hunters" ten years thence gave the ailing Game Boy unusual life, the demand for the game started slow but stayed steady. Demand eventually prompted a patched rerelease (Pokémon Blue) the following year, an extremely unusual step in the cartridge era. This unusual demand meant the television series was quickly greenlit, and Pokemon: The Animated Series took off in 1997 - just in time to be translated for the US release. Unlike the stories of everything else in Gaming's top 10, there were no murderous killer robots, swordfights, aliens come to destroy humanity. In that first season, Ash Ketchum crashes a bike, huddles in a shelter, gets lost in a forest, falls down an increasingly unlikely number of holes, talks to ghosts, and all in all makes little progress at all on his goal to become a Pokémon trainer. It worked quite well - it recalled the Robinsonaide and the Boy's Travel genres, once seen as long dead, and revived them with the power of friendship and merchandisable creatures, and even scandalous episodes couldn't stop the heartwarming tales from leaving lasting impressions. 25 years later, Pikachu's red clown cheeks are everywhere.

But the anime lied.

The stories of the games little resemble the story of the anime; in the anime, Ash is on his own until he reaches a town, while in the games, we wander through the theme park version of real world locations, never far from an adult we can beat up for some lunch money, never far from another enemy-of-the-week encounter pushing us towards the next badge. The anime sold us on a story of coming of age with weird friends; the games sold us on capturing friends and trading them away for merits. But we wanted that game. We wanted to explore; we wanted to test ourselves. The anime made us want to explore; the game wanted us to accomplish. We wanted the sensation of exploration that the hit anime sold us on.

Since being codified, there have been no end of mon genre properties. Digimon, Monster Rancher, Nexomon, Slime Rancher, Ooblets, Monster Sancturary, Temtem, Yo-Kai Watch, Coromon, Marapets, Neopets, Medabots, Magi-Nation, Chaotic, Monsuno, Huntik, Tomodachi Monster, Monkart, Slugterra, Invizimals, Angelic Layer, Duel Masters / Kaijudo, Bugsnax, Cassette Beasts and Fighting Foodons, just to name twenty-five. There have been fanmade games approaching the "Boy's travelouge/robisonaide with fantastic friends" story told by the first seasons of the anime; "How You Survive A Pokémon Journey" comes close, letting us play out the stories of being alone, afraid, and lost, only our new friends to protect us. But no commercial property ever quite came close. After all, there was merch to sell; several properties in the list above started off with plush animals, or card games, or comics or TV shows or other toys before the game ever released. There is always a new zone, a new battle pass, a new universe, new cosmetics, new loot boxes, new releases, new new new new new, and it's always part of a Account with a Social where you can make Friends and engage in Exchanges to complete your Dailies to encourage you to never turn your eyes away, to make sure you wake up to the brand and go to sleep with the brand, never departing until your credit card has drained. Why sell stories about being alone when you can sell stories about being on grand adventures with merchandisable friends?

But then, there was Palworld.

The initial reviews were dark: "It's Pokémon with guns!" many reviewers decried. "Asset flip!" others bemoaned. "Made with AI" was bandied about in some corners, lack of evidence (or even an explanation about what that could even mean) be damned; "Video game slavery simulator" was peddled about in others. But the few streams I tuned into didn't seem to have that in mind at all; from the social interplay, it seemed more like a Minecraft stream. And unlike Minecraft, it looked pretty. So I grabbed a copy to check out what the "antithesis of Pokémon" was all about.

This review contains spoilers. Themes of violence are discussed.

The opening of the game recalls Link's Awakening for how much there isn't. You wash up on a beach next to a crashed boat; three Pals are looking over you as you wake up, but are scared off as soon as you come to. You realize you're shipwrecked, you're abandoned, and the only clue you're given is an abandoned pad with the words: "The towers are the key... the tree holds the truth." Once you gain control, you're put in a dungeon-like room, at the bottom of a winding staircase; the only way to go is up towards the light. Follow the staircase, and you alight on a landing. In the distance, you see an ominous volcano, a Yggdrasil-like tree, and a tower with an interlocking diamond design; but these things are far away. In front of you from your lofty perch are acres of rolling countryside, then dense forest, then jagged crags, then stark snowy mountains. The entire map was setup to provide just this view, a preview of the journey you'll take.

This prologue has lasted sixty seconds. And now, you're set loose on the world.

Of course, there is the obligatory tutorial checklist in the top right corner, offering you some set bennies for going through the game's basic motions. There are some Lamballs nearby - Lamballs being the spherical approximation of a sheep, and this game's most common com mon. Hit some with a stick! And you could quite well do that, at which point you'll learn the Pals of the world aren't static; they fight back, they dance around. Some might taunt you, some might pretend you're not there, some might bark to summon more. Lamball has a spinning attack, Roly Poly, that turns it into a charging damage AOE -but which ends with Lamball stunning itself with its dizziness. A few dodges, dives, and some mutton pocketed later, and you might be ready to move on to the Chikipi - the Pal equivalent of a chicken - or Cattiva, the low level feline predator you might find hunting either.

Maybe you pause and look at that build menu. There's not much unlocked, but all it takes to explore it is to mouse over any options. There's quite a lot you can build with just stone, wood, and Paldium ore - all of which are lying around - and you can begin building a shelter, even levelling up, before you ever go off chasing the Pals of the island around.

Maybe that statue of an eagle draws your eye. When you look at it, you see its crest is the same linked diamond logo as in that evil looking building on the horizon. It gives you a prompt, and you are rewarded with a 'Technology Point', which invites you to look into the game's one-directional skill tree: a technology level slowly counting up and the tools you can unlock.

Or maybe you don't go down that hill. Maybe you turn left when you reach that staircase down, and you see an "Expedition Survivor" - one of the game's many enviromental NPCs. A conversation reveals that you're "another" castaway, and that Pals may not be as innocent as you think - and that Pals are not well-loved in the world; openly carrying them around might draw some attention you're not ready for. But his dress and his words may come back to haunt you later, his words cast in doubt by later actions.

Perhaps you're the kind of gamer that ignores any offered directions. Perhaps, when you see a staircase going up, you immediately turn around and try to run back to the beach in the cutscene. When you do, you find a memo - a log from the Castaway, one of the many perspective NPCs you'll learn about through correspondence. They were in much the same situation as you - and as you explore these nooks and crannies, looking for safe out of the way spots, you might find out in advance about the foes he faced. As you play, these missives expand to other characters - even your enemies.

You might be the kind of gamer that immediately tries to go out of bounds. You are in a mountain; can you get to the top of the mountain? And lo and behold, you can. You don't just have the ability to climb up on the scenery - the climbing animation works just about anywhere, with an interface for switching between standing and clinging to the rock that is simpler and more intuitive than games actually about climbing rocks (looking at you, Hinterland Games). There's a stamina bar, but you'll only see it once you're more than halfway through; most UI elements, from encumbrance to HP flash to stamina, don't bother to show up until you're risking your limits, reducing the number of things you need to track. You can climb that mountain all the way to the top, taking breaks to catch your breath when you find platforms and mounting the ledges with each new motion. You'll find a Pal egg or two along the way (perhaps yours will be Electric, or Fire, or Dark; mine was Rocky). At the top, you'll find ruins of a castle or a lighthouse; there you'll find a Lifmunk Effigy, with instructions to take it to a Shrine of Power to upgrade your capture power. A little picture of the Shrine shows up briefly, and off you go to look for one of the abandoned churches in the game.

Maybe when you begin a new game you just hit escape, and go to set options. There, you'll find the first menu contains a "Survival Guide." This survival guide has dozens of pages, but the first four are clearly marked without any further digging: "Keyboard", "Controller", "Game Objective", and "What should I do first?" They're each under a page, easily read on even the tiny screen of a Steam Deck; there's no Prima Guide, missable tutorial, or Fandom wiki (with all the trackertisement kickbacks that implies) here. No matter what direction you turn your attention to when you hit start, Pocket Pair has put a breadcrumb of information, a tiny reward for looking further, a bit of story, a bit of lore, a big more of a grasp on the giant buffet that is the game's systems.

. . .

Level designers far more experienced than me and game pundits far wiser than I'll ever be have put long hours into the theory behind how best to convey a game's themes. That's because predicting players is like herding cats. From the moment the player gets priority, the well laid plans of game developers go out the window. To handle the priority problem, games can take one of two paths: they can put off the player getting priority as long as possible (sometimes for literal hours, in the case of Final Fantasy XIV), or they can make every path foolproof to give the player priority as fast as possible.

Of the two, the first is far more common. After all, it's fun to write introductions, it's fun to write elevator pitches, it's fun to put all your big orchestral swells and all your expensive musical talent (compare Death Stranding, the mixtape with a delivery minigame attached) and all your tightest voice acting selling your story. Making big, long intros is good for the suits as well, because when they knock on your door at 5 minutes to 5 on a Friday and say "Give us your report - tell us how much money you're making for us", you can wow them with the prebuilt into and they'll puff their pipe and be quite satisfied, because after all, a game with a big intro must be a game with a big customer base, and the suits will leave satisfied.

The other path involves a lot more work. A theatre or writing major would call that "show, don't tell," but that term is incorrect; after all, this is a mon genre game, and there's an awful lot to tell. Late 90s pop-psych called it "learning techniques." Perhaps a better way to phrase it is to light the walkways: when you don't know what exit someone will take, light them all. It's a lot harder to treat the game like a tabletop RPG; to hand the world to the player and say, "You arrive in a field. Your move." But that's where Palworld shines.

All of these approaches for learning how to play the game are not just valid, but common; there's no right or wrong here, these are all things that happen in any game. The platformer who immediately tries to jump on things, the streamer who immediately goes to set settings; the tired wage slave who follows prompts and lets the game tell its own story, the excitable child who immediately tilts the joystick towards the first thing on the horizon to tell their own story with the shiny rock they just found. And that's why fast-priority games are rare - and often fumbled; many indie games say they want to eschew the long, laborious, patronizing, (expensive) opening stretches of modern triple AAA games, and wind up creating a game that puts information out there, but only in one way. There's a tutorial in the pause menu, which you need to read for a few hours, but then it gets really good. There's a bunch of NPCs to talk to, who each give you some starting loot and a mini-tutorial, but then it gets really good. There's a big flashing circle around the button for the Build menu, and this menu has hundreds of options from the start, but once you have studied that long enough it starts to get really good. The superstore that is Steam is full of endcaps of AAA games, but the aisles are full of long stretches of indie games like this, where core mechanics are missable; their review scores are Mostly Positive by the score, in which some reviewers claim the game is intuitive and easy to pick up and others claim there's no direction and no way to know where to go. It's not that the indie devs didn't care; it's that the devs only put themselves into their own shoes, and didn't layer that information.

For all the core conceits of the game, the developers Pocket Pair layered them in, linking one theme to another. There's ruins, so you know this is a post-apocalyptic game, but the NPCs also talk about how they, personally were affected by the end of the old civilization. You know there's an evil villain group running about, and you'll surely see them if you are the kind of person that obsessively watches trailers for clues, but you'll also see them when you link the idyllic statues with the foreboding technomagical towers in the distance - or if you just jump down off the tutorial plateau and start running in the giant open world fields towards the first building on the horizon, when you might see a group of Syndicate thugs attacking a flock of Lamballs. You'll know combat is a game of areas and lcoks if you just wale on lambs and cats and chickens for a while - but if you are the kind that dutifully follows text prompts and you craft the correct amount of Pal Spheres at the appointed times, you'll be guided to the Paldeck, where the cutesy fluff text doesn't just endear you to your new creatures, it hints at how they're supposed to play.

As you run off towards the horizon, you'll recognize something: I've seen this grass before. Then you'll say something else: I've seen these rocks before. And it's a bit jarring.

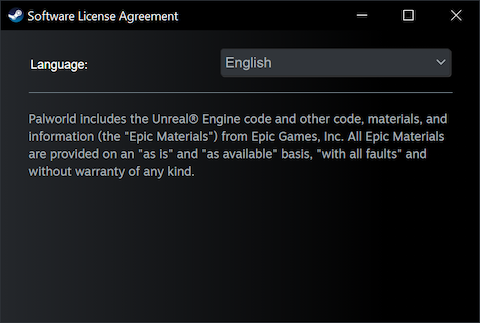

The grass is one of the default assets that ship with the Unreal Engine studio; I believe those rocks are the same. The neoclassical ruins you run through are familiar to anyone who have gone through the Unreal Engine's Tower Defense tutorial. When you arrive at the human settlements, occupied or abandoned, you might recognize elements from the Unreal Engine asset store; they've chosen a mix of beachcomber, post-apocalypse, and medieval assets, probably because those are the cheapest assets on the store, possibly because those elements were available in a Humble Bundle package deal for Unreal Engine assets. At first blush, it might feel like the usual shovelware title. But looking into the places these assets appear got me curious, and I have a different theory about what happened.

This isn't Pocket Pair's first open world survival crafting game. Their breakout title, Craftopia, was "Monster Hunter with tanks": monster hunting and ranching, combined with heavy vehicle and automation elements. The reviews were "Mostly Positive" on Steam, and the individual reviews showed a game far closer to the typical indie game. Difficulty getting started was often cited; a feeling of loneliness and pointless as you left the early game was recurrent. But they made one huge misstep: they based it on Unity.

Unity was, until 2023, one of the premier engines for multiplatform game and app development. It had deep libraries, it had an asset store, it had loads of developers putting in tens of thousands of man-hours of tutorials. It and Unreal were the two giants of the industry. But September 12, 2013 changed Unity's fortunes forever: its executives announced it would begin charging developers per install of the game. A few days later, it announced it would begin charging per run of the executable. Even putting aside whether or not such a marked unilateral change would be legal, or whether such fees could actually be paid by the developers, the bridge was already on fire. And for companies that lean on assets, being charged a hundred dollars per model, fifty dollars per sound library, twenty dollars per code library, possibly taking a percentage cut of all ads, and then being charged long after the developers had received their one and only purchase from a user... well, it was a death knell. Even if the changes had been undone immediately (which they were not; the C-levels chose to jump ship while the stock price was high rather than deal with the backlash), the damage to the company was already done.

As for Pocket Pair, Craftopia didn't immediately get the axe; a major content update with a new area, new Dedicated Server option, new skills and new bosses was added this past December. But the writing was on the wall: any games now based on Unity may very well outlast Unity as an entity. It's no mistake Palworld was moved up from "sometime Q1" to almost immediately after the Unity changes went into effect.

Palworld's first trailer doesn't just have a different logo. It shows a completely different look to the game - a Unity look; the shaders are optimized for mobile in this trailer, with more gradients instead of whole textures; trees are made out of chubby spheres and chonky prisms popping out of fractals, and buildings are isomorphic assets with their own individual construction animations (a la The Forest) not built out of construction components you place and build individually (a la Fallout 76 or Valheim). There are entire mechanics in the trailer not seen in game, like destructible terrain (a type of mechanic Unity excels at, but which the Unreal Engine has less than marginal support for) and fishing. But early on in the development of Palworld, the management of Pocket Pair made the decision to ditch Unity for Unreal. To hear them tell it, it was due to the depth of mechanics; even this trailer shows a wealth of mechanics, and Unreal (being straight C, rather than any more complex or restrictive language) makes it easier on developers to create intricate systems with it. And Unreal is a far better engine for multiplayer gaming (as its namesake, Unreal Tournament, might imply). But with the death of Unity, Craftopia suddenly went from the company's star project to an anchor on the company's fortunes; and Palworld went from a title that was going to be in a slow burn early access period to the game the company is banking on.

It's evident how many purchased Unreal assets are being used to patch over assets that were suddenly locked behind Unity's malfeasance. The grass is Unreal's default cel-shaded style; the ground textures are Unreal's default photographic geography textures, while the trees come from a low-poly set. The characters and the Pals, themselves, were made in-house, with their replete set of animations and facial expressions, in a softer style closer to a faux-animation; the highlighting doesn't quite match the flater shading Unreal favors. But in general, the assets chosen work - things you can interact with (NPCs, Pals, resource nodes, player buildings, attacks) glow, and things you can't interact with (the ground, ordinary plants, NPC buildings) don't; this holds true in all biomes, from the ruins to the plains to the forest to the crags. An artist with more experience than I have could probably talk about collage and deconnexion, intentionally using different art styles to portray things operating under different rules. I'm just going to chalk it up to a rushed dev team making the best of a near worst case scenario of their assets disappearing in a puff of licensing hell, and simply say the graphics work well enough.

Except trees. Trees are weird.

There's a day-night system in the game. And as you wander around, you see the cute Lamballs and Chikipis fall asleep as sun sets - and as the night moves on, more dangerous monsters come to light. Daedreams come out, their hair bobbing in the distance like will-o-wisps; cowardly Cattivas are replaced by the far larger Hoocrates, who always move in pair, and are Pocket Pair's reminder that an owl's primary function is to wreck your face. If you head towards a nearby plateau, you might even find a Nox; the game's Eevee-equivalent, it may look floofy and friendly, like a little gentleman with a cloak - they will ruin your day, what with homing attacks being the signature power of dark-types. My first knockout in the game was caused by thinking the smallest, cutest Pal was the smallest threat. While the herbivores and pack Pals stay to the patches they spawn in, the solo and predator Pals will wander from area to area, and you're constantly listening to hear a new kind of footfall heralding a new foe. There's no obvious shelter. (There are some human settlements, if you are daring enough to run towards the first smokestacks you see. But even if you choose a smokestack that isn't a Syndicate base, wild Pals are not prevented from entering settlements. Monsters have the same freedom of motion as you do; you might wander in a town only to find its occupants dead, if you waited long enough for a wandering monster to tear through the inhabitants.)

Within the first 10 minutes, if you follow the tutorial - or within the first 90 minutes, if you spend time climbing all over the game's architecture and don't think of it until you talk to a Wandering Merchant who wonders hey, where's your house - you'll build a Palbox. Palboxes are this game's core infrastructure. They act as your land claim in the world to allow you to build, they give you your Pal management system (where you can swap between your team, your settlement, and healing in the box), they let you level up, and most important, they let you fast travel to the eagle statues - one of thich is right by the spawn. Fast travel statues are placed about five to ten minutes apart; there's still a lot of ground to cover. But you soon learn what areas are less travelled, and you'll pick a spot to start your first base.

As mentioned previously, basebuilding in the first trailer resembled The Forest: you select a premade assets, you (and your Pals) collect the parts, and the whole structure pops into existance. But the final version of Palworld went with a more typical platform-based system, closer to Fallout 76 or Valheim; you build 10 foot by 10 footfloors, attach various designs of 10 foot by 10 foot walls, and put 10 foot by 10 foot ceilings up. You might even be daring and put up a 45 degree ceiling. You'll fill this shelter with beds, fireplaces, and crafting tables; you'll surround it with farms. Each Technology Level has six advancements, from cosmetics to equipment to structures. Luckily, the categories of Palworld are nowhere near as busy as Valheim or Fallout 76.

While it might look beautiful, attempting to actually use the base builder is where the promise of Palworld strains the most at the seams. It suffers from the same issues as many games with unlimited placement - it's easy to accidentally lock yourself out of better setups, hard to fix them, and difficult to improve without many iterative steps of building, tearing down, and building back up again. But even if you had the time and patience to do this repeatedly, you'll come face to face with a foe endemic to over-the-shoulder open world adventure games: the thing you, the player at the screen, are looking at is not always the same as the object the game registers you, the player-character object moving around the game world, as being able to interact with. I placed my primary crafting storage immediately adjacent to my campfire, and was rewarded by continually accidentally opening my campfire. To interact with the box, I have to circle around the campfire carefully, making certain that the action-prompt is indicating to open the campfire, not to cook at the fireplace; even when the game determines I've visually focused on the box long enough I should be able to see its hit point values, it will take further motion to move my avatar into the right "sweet spot" to actually interact with the storage. And yes, I've had the fireplace prompt open up while I was looking at the storage box's HP, the most jarring example of player visuals versus avatar placement mismatch.

(You'd think I'd just move the campfire or storage. As of review time, your humble reviewer had done neither.)

There's one other way in which the position-sensitive nature of base controls gets in your way: your Pals. When your Pal is directly in front of you, you can pick them up with the same button you use to interact with furniture, F. Now remember, your physical position is not linked to your viewport angle; the pay may not even be on screen when you're hitting F. If your pal wanders in to your Avatar's range of reach while you're working - as you might do when you build a tiny utilitarian base, with everything packed densely together - or when you're done crafting, and you go to pick up the fruits of your labor - your Pals might turn your work command into a Lift command, and you'll find yourself in the middle of your crafting zone with a curious Lamball or Chikipi held aloft. Now you've entered a dangerous position, because the rest of the Pals in your high traffic zone have noticed your Pal getting Uppies. And now, all your other Pals want to get Uppies, and soon you are force to spend time either lifting and tossing everyone who wants a turn of play or literally running away from your own base to avoid giving everyone love.

Yes, there's guns. Deep down in the tech tree, starting at level 25. I can't tell you anything about it; I haven't got there yet. But I got an ancient bow, which I upgraded with some blueprints I found. These are magnificent for drawing aggro in a controlled way; unlike my prior beatstick, which means I have to chase my targets down on foot like some fool. And soon, like any player given a stick and an open field, I run forwards, eager to catch tame them all.

Movement in this game is rewarding. First, it's rewarding in the very literal sense; there are treasure chests and resources scattered around, and even finished resources can sometimes be found in hidey-holes, which means you're encouraged to peek into nooks and crannies, to go down canyons instead of going around. But it's also rewarding in that movement, itself, is fun. As mentioned above, there's a deep climbing system integrated into most of the world; you can scramble over walls, trees, your own structures, giving most pathways a "high road" that's relatively safe and a "low road" that's full of Pals and prizes galore. Not too deep in the technology tree, you invent a glider; it's similar to the glider yous ee in the original Unity trailer for the game, which in turn was most likely from the glider seen in 2017's Breath of the Wild, encouraging you to make that wild jump, try to cross that gap. There's fall damage, but it's forgiving - so long as you don't land on a Pal, that is. The two systems intertwine because both key off of the same resource; as long as you have stamina (one of the player stats you can improve as you level up), you can continue to hang on to the glider, or you can continue to hang on to the ledge. You can chain from one to the other - if you decide to sprint up to a ravine, pop your glider to build up distance, and latch onto the far wall, you can keep climbing once you get there. There have been a few nasty spills and some awfully close calls, but it's imminently rewarding to Evil Kinevil my way out of danger.

But that's not all - sprinting uses the same stamina as jumping or gliding, and it, too, can interlink into the same chain. When you sprint, you can crouch; this converts your sprint into a stylish slide. And, just like in Apex Legends (the game that made the crouch-slide de mode), sliding downhill actually speeds you up. You can jump into the air, conserving that momentum as you spring forwards, and pop the glider - and be moving through the air at the grind speed while flying over obstacles in your way. And if you still have any stamina left, you can use it to connect to a climbable surface (almost all of them) and make it up to the top, using sprint-dashing to make it from place to place.

(Swimming, too, uses the stamina system, but it seems incompletely implemented; there's a diving animation for when you aim towards the water and sprint down, but you immediately bob right back up again. Perhaps swimming with my Celarays is something to look forwards to in the future.)

There's a fast travel system; the Eagle Statues, which you are introduced to right after the game's start, are spread out across the map, and unlocking new Eagle Statues is the surest way to gain extra Technology Points. But your goals are probably a bit of a hike, so there will be a lot of overland travel; between the distance to the nearest Eagle Statue and the sheer fun of getting to max speed in a glider and launching yourself at your target, it's entirely possible to forget that the fast travel network exists. Other than using the statues as a way to fast track back to my Palbox to heal, I didn't use the statues much; I much rather would prefer to see the places between than to be whisked from place to place.

In and above all the things you can do by yourself, or with equips only, several Pals in your team can be mounts. I have a Chillit, which is an icy-blue ermine Pal, but giant; he's not significantly faster than I am, but he has a lot more stamina, and can sprint across fields I'd have to rest 2-3 times to cross alone. There's a glider upgrade, as well, which uses a Pal; instead of hanging on to a leather frame, I can let my flying Celaray take me instead. Each individual breed of Pal needs its own tech (usually a specific saddle, harness, or gloves), so you can't just grab a new Pal and immediately use them like a new car.

As I ran around the world, I soon realized something important: the position I chose for my starter base sucked.

In this particular case, my instincts gained from other outdoor survival games led me astray. In Valheim or 7 Days To Die, you want your home to be far from resource nodes; if your land claim is too close, your land claim will overrule the resources, and following those instincts, I managed to choose a near-barren plain with only a few rock nodes to work with. I didn't want to move my Palbox (even an half-hour's worth of sunk cost fallacy is a thing), so I was winding up moving farther and farther afield to get Paldium and Ore; even wood sometimes necessitated a run, when my Pals cut down the only trees in my tiny starter patch. I catch a Cremis (the daytime counterpart to the Nox that annihilated me), a Teaphant (an elephant that is a teapot), and I get my face wrecked by a Tocotoco (parrots with a bad case of the explosives). I'm beginning to get despirited. This wouldn't be the first time I got snookered by a game with pretty graphics but paper thin mechanics; my time spent with Forager was largely wasted, as I went through a beautiful world only to take damage - repeatedly - and watch numbers go up - slowly. There was no whimsy, no joy, no reason to continue other than the occasional bleep of an achievement, and Palworld started to feel the same way. Is this just another collectaton? Is chasing level-ups the only thing this game has going for me? My mind wanders to the refund button.

I go off to collect some ore. Along the way, I find one of the wandering solo Pals - a Dinossum, a plant-type Pal resembling a brachiosaurus covered in leaf 'scales'; it was level 17, and I was level 8. It wasn't a good idea to take it on; I hadn't crafted armor, my weapon was still on that starter "random beat stick", and I had been avoiding anything that looked bigger than me. But this one looked just big enoughfor me to capture. It wasn't easy, but between a bit of geometry abuse (always look for the high ground) and carefully cycling out my pals (none of mine were especially effective, but I could swap Pals around between dodges), I was able to trap it in a Pal Sphere and tame it.

And... that was it. Another number in my palbox. All the trouble of the past few minutes, just for my quarry to disappear as anticlimatically as a 'mon being sent to my PC.

Returning back to my base, I made some team swaps (putting my injured Pals in the Palbox to recover), and added my new Dinossum to the team. In a final insult to injury, I notice my Dinossum is being affected by Level Sync; it was defeated, so its effective level is now lower than its true level. All that time and trouble to catch a giant Pal to emulate some of the physics-abusing actions indicated by the giant Pals of the trailer, and I don't even get to use it. That refund button was certainly big and shiny.

I went through the rote checks of my base: there were complaints of hunger, probably because I spent twenty minutes waling against one Pal instead of tending to my herd of Pals. I went over to a farm plot and started tending to it, holding F for the requisite amount of time to seed the plot. But then I heard a chirp. My Dinossum saw what I was doing, got a surprised look, and came bounding over; as I continue to work, it began to spray a sparkling breath over the field, and my planting speed more than doubled. We completed the task, and the Dinossum's face lit up; its eyes sparklde, and unexpectedly, I got a notification from the game. I looked at its stats, and the level sync is gone. Its mood had immediately cleared up, and instead of a dark, dour, wilted beast, I have a bright, flowering Dinossum, who eagerly followed me to the next field so it could help me with that one, too.

None of these elements were linked - or scripted. There was no Grand Art Director saying that we players should learn to perform a farm loop from a tutorial video (looking at you, Valheim), or from being told by a grandfather figure (looking at you, Stardew Valley). There were only actions, and consequences. My Dinossum was knocked out, so it was sad (and afflicted by a level sync). I had to feed my Pals, so it came back to the base. I was farming, so it had something to do. It got to work with me, so it cheered up. It got cheered up, so its level sync faded away. The developers at Pocket Pair didn't write scripts; they wrote consequences, and I could have found them at any time. But it was my choice where to find them - and my reward for their discovery was not numbers or achievements, but my Pals' happiness.

And suddenly, the entire game opened up to me.

The core loop of the base building is to make space for Pals; the more key amenities you have, the more Pals you can sustain. In turn, the core loop for Pals is to give them the four things they need: somewhere to sleep; something to eat; something to do; and somewhere to relax. Not all Pals can do all tasks; the Teaphant's tiny stubby hooves mean it can't do handiwork tasks at all, but its giant trunk means it excels at Watering tasks. Most Pals can't work the forge, but the fiery Foxparks works it and the oven with gusto. Lifmunk can do Handiwork, so it can help me craft; Daedream can do Handiwork, but it's also strong enough to help with Transporting. Tombat can't do handiwork at all, but its giant claws means it excels at transporting.

Not all Pals are satisfied by the same things, either. Most Pals can eat Red Berries (the game's basic food), but some like it less than others; Dinossum gets almost nothing at all out of it, which makes a loose sense when you consider that a flowering Pal is probably made of berries. However, some fresh or baked mushrooms make Dinossum perk up quickly. Roast Lamball or Chikipi kebabs (harvested from wild Pals I decide not to capture) satisfy most carnivores. (To my horror, I discover that roast Lamball shanks immediately fill a Lamball's Happiness and Satiety to above 100%, which either means there's a big bug that made it into production or there's something horrifying about sheep I'm unaware of.) As of right now, I've only made two different relaxation areas: a hot springs and a training dummy. (My hands might count as a third relaxation area, for as much as several of my Pals like to insist on Uppies when I'm working on something else.) But I won't be surprised if in time, my Pals show distinct tastes in how they relax, too.

As your Pals do things, and as you do things in the same base as them, Pals level up. When they level up, they unlock personality traits (here termed Passive Skills), which gives them slight benefits. Unlike "Natures" in Pokémon, Pal traits can be strictly positive or strictly negative. For example, my base's main handiworker, Cattiva is Conceited (a +1 trait) and Downtrodden (a -1 trait); being Conceited means it gets +10% work speed and -10% Defense, and being Downtrodden gives it a further -10% Defense. It would never be a good choice for a front line team, but it's quite happy moving materials around within my base. In and above the numerical attributes, there are also behaviors attached to the passive skills your Pals learn. One of my base's main transporters is a Celaray, a swift flying manta ray; as it levelled up, it developed the trait Clumsy. This means that, in addition to a flat -10% work speed penalty, it would occasionally just drop everything and spend the next 20 seconds of its life unable to pick things up, as any pickup behavior would immed3iately be followed by a drop. This resulted in my butterfingers of a Celaray spreading showers of rocks or wool around the base until other Pals could help it clean up. Again, that last sentence was a result of Pocket Pair writing consequences, not instructions. That little scene of emergent behavior wasn't written into any script anywhere, but the sight of my little Celaray going "whoops!" and cascading rocks all over is now engraved into my memory. Sometimes, these Pal skills improve your abilities; Motivational Leader is a +3 passive that gives the player +25% work speed, while the passive Stronghold Strategist gives the player +10 Defense. (I lucked out into a Lambroll with both traits early, so I spent an awful amount of the early game with a spherical sheep as my main companion in arms.)

If you're the kind of gamer that maximizes IVs, you'll probably do deep dives into the game's breeding system, in which you can combine Pals with ideal traits together. A +12 Pal (with 4 passives at +3, the theoretical maximum) will probably be as difficult to get - and as treasured - as a Pokémon with perfect IVs But despite the character it threw into my Celaray, this system does not require deep inspection to exploit; I wasn't required to maximize anything to move on, just play a bit wiser.

There are other humans in Palworld; the most benign are the sole survivors, and the wandering merchants that travel between them. But the most common is the Syndicate.

The Syndicate don't have voice lines (no NPC does in Palworld.) But you can get a handle on them pretty quickly. For one, unlike all the other humans, they have guns. For two, also unlike all other humans, they're quick to train their guns on you. And finally, you don't need a collegiate degree in symbolism to realize what a black, white, and red themed enemy force is coded to resemble. They move in packs, and the roving gangs are the most overtly obvious evil in the game.

The first time you encounter them, they might not even attack you. But the sound of guns going off in the distance will draw your attention quickly, and you'll see a band of four or six syndicate members taking on a high-level Pal. They may not win. (My first time encountering one, they had made the decision to take on a Mammorest, the pine-mammoth hybrids you might recall from the title screen or trailer. This encounter did not end well for them.) But you don't get enough time to simmer on that; soon you will get a warning that the Syndicate are attacking your base. These raids can take place wherever you are, whether or not you're ready for them. I wasn't too far from home at that base, but luckily, you get a brief reprieve, as your attackers enter the world hundreds of meters away, giving you a bit of time to prepare.

Unlike other humans, the Syndicate are after the same goals you are: they want to capture Pals, and by that point in the story, you've collected a fair few unique ones, and put them all in one place. They'll try to capture them. But unlike Pokemon, you're not alone. All your Pals, that have been levelling up while you roast berries and turn iron ingots into nails, will come to your defense when you or an allied Pal are attacked; the Syndicate, in return, make dutifully satisfying "WHARGARBL" noises as they get defeated in turn, leaving high end treasures ("ancient crystals" - spark plugs - and a smattering of old coins) in their wake. After an attack, some Pals will need to be rotated back to the box to heal; others can come out to explore.

But, in a bit of catharsis, raiding bases goes both way in this game: they can strike you, but you can strike back.

Throughought the world, you might stumble upon campsites. These campsites include Syndicate members with grenades, or greater fire rates, or stronger guns; and these bases are overtly fortified, with defenses to duck behind, walls to cruch behind. (And just to clarify this statement, Palworld is not a cover shooter; you're not selecting between setpiece hidey holes until you have defeated enough foes to reach the Ultimate Setpiece Hidey Hole, as if the game were a Far Cry tower collector or a high-res remake of Sentinel.) These combats rely much more on using cover and managing your exposure from moment to moment; Syndicate members might be flighty in actually attacking but their shots don't give you room to hit. Upon clearing out the base, you might find a captured human, and free them for money - or a captured Pal. These pals can be species not native to your local biome, and might have unusual modifiers; these "special Pals", when rescued, join you. That's how I got my Rayhound and my Fuddler; my Rayhound hasn't seen much use, but my Fuddler is a joy around the base, using his giant sloth-otter claws to dig and scoop.

As a result, I am now constantly on the lookout for new Syndicate bases - even if the numbers are bad - because beating up poachers and freeing their quarries is, by far, my favorite way to recruit Pals. And technically, that's all you need to do - you can leave those starter Pals alone, dig and craft, and let Pals join you freely. Palworld is a mon game where you don't have to capture anything.

There are scant few musical cues in the game; the OST lists 17, but I've heard four. There's an opening theme, a battle theme when something has started combat against you, a field boss battle theme, and a Syndicate battle theme. But despite the lack of music, this game is far from silent. Ambient sound design is one of Unreal Engine's core strengths, the editor giving you plentiful ways to review and manage sound nodes as easily as it manages behavior nodes or map objects, and Pocket Pair leaned into that; the wind blows over crags, rustles trees, makes brooks bubble. Birds call at sunrise and sunset, and beasts occasionally howl at night; you hear frogs and bugs in the distance. Seven Days To Die, it is not. But it's not just a stage element, because Pals make noise - and they feel just as alive as the trees or terrain.

Pals make a noise when they wake up, and when they fall asleep. They make a noise when they're startled (like when you suddenly enter their field of view), which is not the same as when they're curious (when you or your Pal make a signifcant noise or accidentally leave crouch in their hearing radius). They make calls as they attack, and they have distinctive walking sounds. And this led to another "game opening up" sequence.

I was heading towards a rare Pal node - a spot where more powerful Pals are likely to spawn, hoping to add a strong Ice type to my team. It had gotten dark, so I recalled my Pal back to my Pal sphere and decided to hoof it. Sunset had fallen; the sun had gone down, and I was pathing along the rocky outcroppings to avoid more poorly lit, more densely populated forest floor below.

A new sound stopped me. A footprint, but not like the Chikipis or Rushoars I was avoiding. It was deeper in pitch, softer in tone, and the steps were more frequent with less duration. It sounded like a dog. I turned to face it, and carefully headed towards the source of the sound-

And came face to face with a Direhowl. You can probably guess what it looked like by the name alone: great big black-and-white canines, large enough for the player to ride on, large enough to digest the player.

Then, I got treated to quite a few more sounds as it barked, which was followed by various running sounds as the pack (of course wolf-archetype Pals have packs) came after me. Then more sounds as I ran, not quite able to deal with three Pals three levels higher than me.

Unlike the tale of capturing the Dinossum, I don't have any heroic tales to tell; the pack wrecked my face. But that entire encounter happened because of the sound design, because the world made me curious.

The tutorial ends with a single task: defeat the boss of the Rayne Syndicate tower, the giant tower you saw in front of you when you first climbed out of the stairs. While you can use the same wall-climbing, glider-flying, clever-exploration techniques to get to the tower, the tower itself is an instanced area. You've come across a few of them by this point; some of the rarer Pals don't wander the world map, instead holing up in castles or caves, with their fights taking place in instanced rooms.

When you fight Zoe, she summons her signature Pal, an alpha Grizzbolt, from the same sort of Pal Sphere as you have; and unlike every other Syndicate member, she hops on, forming a part of the boss battle, your first true Tamer on Tamer fight. It's not just an increase in hit point pools (although Zoe and Grizzbolt certainly have that, almost ten times the hit points of a typical Pal their level); they have a broad spectrum of attacks. Macrossing bolts like Pengullits, slow moving damage orbs like Daedream, slow-charging laser rays demanding cover like Syndicate snipers, rapid attack stomps slamming you like Dinossum, and cascading bolts of electricity racing down, it's about more than just beating buttons; you'll have to use the scant cover in the arena, while cycling out your Pals, making certain none of them pass out and head back to the Palbox to recover, using all the skills you practiced in the Syndicate base raids and fighting the rare giant Pals to whittle the duo down.

Palworld pulls you out of the fight - figuratively, with the game being over the shoulder, showing your avatar as a third person; and literally, with your Pal being the primary combatant. Even early on, your Lamball has the field skill "Fluffy Shield," allowing you to use your Pal for defense; but you have to watch for your Pal's health, too. By the time you've reached Zoe, your Pals have long, multi-attack chains, cycling through melee, ranged, and AOE depending on breed. Your goal, at that point, is to assist them - to fire shots to take out stragglers or stray aggro, to line up critical hits that might stun when your Pal goes for one of their bigger attacks. In effect, they're the main tank, and you're the opprotunistic lancer (as well as support, switching your Pals out to let the others rest).

The fight against Zoe was a skills test culmination that actually tests you, a refreshing changeup from the learn type-exploit type advantage-win days of that other game. But as I beat Zoe, I flinched. The final item in the tutorial was heading away. Was it going to be replaced with a new checklist? Was someone going to greet me at the entrance and say, "Your answers are in another tower?" I recalled my Pal and prepared to head up, exiting the Tower from a one-way door at the very top. And instead of being told what to do, where to go... I got to see again. Below me, the world of the Palpagos was once more spread out, an echo of the view at the top of the the Hall of Beginnings at the start of the game. The volcano, Yggdrasil, and further towers were now visible from my high vantage point; new threats, previously concealed by the crags at the foot of the Rayne Syndicate tower, were now lain out before me.

But more than just a shift in vantage point, the same view as before was now filled with more details. I knew that the green golden spots were Lifmunk Effigies, and that I could climb to each and every one of them to improve my powers. I knew that the red spots were Eagle Towers, and I could unlock them to expand my fast travel network. I knew that the smokestacks were from human settlements, and that those could be friend or foe. All the same elements were there just like before; but this time, there was more knowledge. I was beginning to master the world that Palworld had set out for me.

This game straddles two genres where gamer expectations have never been high for new games in the genre: the mon genre, and the open world survival crafting genre. (They're also the shortest and longest genre names I know if, respectively.)

For the mon genre, new games in the type are often looked down on because the developers look down on the genre. Ever since an old Comedy Central low-budget animation used the relevance of Pokémon to get some real old-timey racism past S&P, the number of dark, depressing, and downright mean-spirited mon clones has never been far. Evertale purports to be a monster collection game, but with hentai and RPG Maker horror elements. The first tabletop game to handle the genre was called "Cute Fuzzy Cockfighting Seizure Monsters." PETA made two of their own, which is all I want to say on the matter. Cartoon Network made their own 'mon game based on their science fiction horror cartoon that sounds like a 70s sitcom, simultaneously taking shots at it while hoping to get some of that sweet sweet microtransaction dollar. The genre's been targeted by everything from sitting Congresscritters to College Humor, and no claim has been too absurd, no insinuation too wild, that someone hasn't laid it at the genre's feet.

But despite how lucrative hating on the genre is, and how hidebound the few kings at the top are, the mon genre is still full of new indie darlings: games that are a dev's first released game, and unfortunately, usually their last. Most of these games aren't poor due to malice. After all, everyone who has ever downloaded a copy of the Pokemon Universal Construction Kit has set aside time to make the perfect starter town, maybe the perfect first encounter with a truly engaging villain, before we got tired of fighting with RPGMaker's opacity. We hold on to the games that try sincerely (Temtem and Cassette Beasts are currently tops in the charts, and I will sing the praises of Kadomon to anyone who will listen despite it looking like a 2D asset flip), and even the games that fail often have endearing qualities (the retro fidelity of Nuumonsters, the story of Nexomon). Mon lovers play them, beat them, but ultimately put them on the shelf. There's some cute designs, but even the most diehard fanartist might only make one or two pieces before they grind to a halt against a game with no spark, no joy, no whimsy past mission complete.

Things are less rosy for the open world survival crafting genre: there, care is a rarity.

Starting with the original asset flip open world survival crafter, Rust, the genre has long been the siren call for companies with ambitions of a big payday but little budget to make it happen; after all, these would-be instant millionaires tell themselves, Minecraft looks terrible. Just buy some assets using a credit card, and they'll pay the credit cards off when they make their first billion. And so, the genre fills up with games like Fantasy Craft, Under a New Sun, Cubelands, Mineblock, Blockmania, Minebuilder, Craftworld, Cubeworld, Fortresscraft, Blockworld, and Survivalcraft. Any little success that breaks the mold is rapidly iterated on. After the "success" of 7 Days To Die (a open world survival craft game with zombies), the genre filled up with games like Zombie Apocalypse Survival Simulator, The Day Before, Castle Miner Z, The Walking Zombie II, The Infected, Survivalist: Invisible Strain, and on and on and on and on and on. Any hint of playability or whimsy or novelty is whittled out, beaten out of the devs' hands, because management don't want new games - they want safe games, games where players tired of their current open world grind might be enticed to grind some more here, and just coincidentally spend some money in their particular microcurrency shop. Grounded won awards a few years ago for combining the open world survival craft with Honey I Shrunk The Kids of all things, and the reviews for that game noted it wasn't terribly fun or unique when it came to the mechanics - but it was stylish and different, and that was enough to endear it to the beleagured fans of the genre with few wins and many losses among their numbers.

(Palworld has no shop, no microcurrency, no DLC, no lootboxes, and charges no fees to run your own server. It does have an active mod scene, however, which is a striking statement for a game a week old.)

Right now, Valheim is the newest and brightest star in the open world survival crafting genre, but space survival like No Man's Sky, Astroneer, and Life Not Supported is getting big; Volcanoids, Voidtrain and Frostrain are recent train-survival darlings; and the hard-to-quantify Timberworld is hot on everyone's heels, so I fully expect the next big glut of asset flips to be beaver space train viking open world survival crafters. But then again, even the game Palworld most directly descends from hasn't been doing too well.

The latest generation, Scarlet and Violet, has been given blasted with poor reviews. (Metacritic does not normalize their scores to a percentile scale, so a game with a rating below 75 often has significant issues; the user generated reviews on Metacritic are not so constrained, and can be far harsher.) Performance issues were common; issues with objects disappearing, even when the player was looking at them, was common, and the official guidance to prevent the game from crashing was to periodically close and reopen the game. The previous generation wasn't much better; Sword and Shield shipped with a bug that could hard crash and corrupt the Switch filesystem upon loading a game, a bug that Nintendo charged per unit to fix.

In and above all these issues, the amount of polish put into mainline Pokémon games has been steadily going down. The first generation of games gave its species portmanteau names that often combined classical roots with anglicisms; thus, we got fictional names such as Bulbasaur, Charmander, or Squirtle; nouns that played by the rules of English common nouns, yet were evocative. In contrast, the latest generation as of this writing featured names that seemed simply transliterated without translation (like Chi-Yu or Wo-Chien); others are literal translations, with no attempts to make them fit into English common noun nomenclature (like Iron Moth or Great Tusk); and many of the 'paradox pokemon' simply seem to be using beta models (such as Gouging Fire the non-Entei, and Wigglett the non-Digglet). Which is not to say variations are unknown or even foreign to the Pokémon franchise; regional form variations were welcomed by the Pokémon playerbase as a way to explore existing ground. They had the existing system... The Pokémon Company just didn't care. The amount of telling instead of showing has simply gone up, and this telling is increasingly machine-translated. And the prices for the games are steadily going up in return for the lack of polish, with the latest game requiring a $40 DLC, plus ordering sight unseen to receive a preorder bonus, plus $3/month for the backup service (which only backs up pokemon you intentionally place into the box, as everyone whose consoles got bricked discovered).

But they also sold 10 million copies in pre-orders and their launch weekend, making this 'only okay' game a billion-dollar success, so The Pokémon Company is unlikely to ever change their ways.

In the interim, Palworld straddles the two genres, trying to appeal to both. To the open world survival crafter, whose players are often beleagured by the feeling that the game is little more than kneeling at resource nodes until the game lets them move on, Palworld offers the mon genre: mons who will hunt for you, cook for you, mine for you and gather wood for you, so long as you give them berries and Uppies. To the mon hunter, whose players are often downtrodden by a world as flat as Pokémon card stock, Palworld offers building in an open world: rewarding movement, foes to seek out and foes to defend against, and a world that is made for exploring. The developers and designers at Pocket Pair have found a combination of genre's where one genres weaknesses are covered up by the other genre's strengths, papered over the awkward bits with clever interactions of behaviors and genuine heart poured into small touches like animal-like vocalizations, interconnected behaviors, and whimsical animations. Once you feel it all moving together in action, the "weird combination" doesn't feel so weird at all anymore.

As of this writing, I've put about 26 hours into the game, and have nearly reached level 16, purely in singleplayer. Despite the memes, I have yet to give a single Pal a gun. I've just about finished the first island, save some secret bosses I cannot quite handle yet. I've built a sustainable farm, where grass types sow seeds, water type hydrate fields, dexterity types harvest the grain, and fire types cook it; I don't have great defenses, but I have a great community, and it works to fend off wild creatures and Syndicate raids for now. I know something about the first island's boss, the eminently reasonable reasons she joined up with the villainous Rayne Syndicate, and exactly how much that oh-so-justifiable deal with the devil cost her. I know the attack patterns of many early Pals, and I am not shocked (as often) when I encounter a new species. My gear breaks all the time, I keep having to hoof it back to base to tend to an illness, but then (after a few minutes to make certain the ovens and farms are in good working order, making certain my Pals are healthy, perhaps talking to a wandering merchant, and perhaps giving one or two sad Pals treatment for their often acute cases of Want Uppies) I get to head right back out again.

Right now, I am making scouting expeditions. The game's map showed me six islands, other than my starting island; however, there's huge holes in that map. I still haven't figured out where the base of the volcano or where Yggdrasil is. And I've begun seeing concerning flashing in the moon, once an in-game week, patterns that suggest that the map I have now is not the only map I will ever have. These expeditions have given me a vague idea of which islands I'll be able to move to soon; I know which ones will just smack me right back into the ocean, and which ones I'll be able to make inroads on, given a little prep training my Pals for some type advantage to make a foothold. And I've made first contact with some of the other human factions on the Palpagos Isles, some friendly, mostly not.

And all this happened without a cutscene, without a narrator, without any text scrolls laying out instructions, and without any mysterious road blocks keeping me from stepping too far out of the walled garden. I was never told by a narrator "You must whup the five Bad Guys of Destiny, and collect their badges." It was all available at the beginning; only my own skill kept me from advancing. But the game gave me plenty of ways to improve and advance, and these elements were reinforced by the other elements of the gameplay. There are new Pals to meet and capture; some I want because they're cute (there's a chonky flower goat I'd love to have at my base), some I want because they'll expand my power (I saw something that looked like a flaming deer I'm going to try to catch to have more than one Fire type Pal), and some I just want because of spite (I will never forgive the entire Cinnamoth species for the time a level 20 moth knocked me off a cliff at level 9 when I was low on stamina, and every one I hunt one down, I hope the one that knocked me down learns that I am coming). But there's no time pressure to get there - there's still plenty of mountains to scale, dungeons to explore, islands to reach, with my Dinossum by my side. And maybe I'll just take some time to cook berries for my Lamball ranch, to impove the house I'm building in the forest plain, to defend my home and welcome new Pals into my little towns. There's time enough for that, too.

Because Palworld is the antithesis of Pokémon. Palworld doesn't want to tell you how to play on its terms: Palworld wants you to find how to play, on your terms. And it will greet you halfway, to reward you for searching.